Examining Lyme Spirochete’s Bag of Immune-Evasive Tricks

Before stepping into the ring to take on patients who might have Lyme disease, I conducted my own review of the literature on the immune evasiveness of Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), to see how this spirochete causes so much confusion and trouble. That was a sobering experience. What follows is a summary of things I learned about Bb.

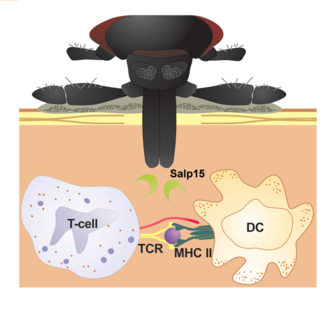

What happens within the first 72 hours after a deer tick starts to feed on you.

|

|

Illustration by Christian Stutzer |

The Delayed Antibody Trick

As your blood signals reach the Bb in the tick’s midgut, they mobilize. As they pass through the tick’s salivary gland, they pick up a protein called Salp15, which masks a Bb outer surface protein known as OSPc (by binding to it). This makes OSPc invisible to your immune system. That’s bad because detection of OSPc leads to antibody formation. If OSPc is not detected early, then your antibody response will be delayed until Salp15 degrades, making OSPc detectable. This gives Bb a head start on escaping your circulation to its way into your connective tissues, where there tends to be substantially less immune cell traffic.

The Hall Pass Trick

The innate immune system is factory-installed and ready to operate at birth. It’s genetically coded to recognize dangerous molecular patterns and disable their sources. When an invader is detected, the innate immune system launches a cascade of proteins from what’s known as the complement system. This system unleashes a potent defense by forming membrane attack complexes that dismantle the invading microbes. The reason this system avoids damaging your own cells is because they wear a badge called Factor H, which says, “I’m on your side. Leave me alone.” By its ability to bind Factor H, Bb dons a hall pass that allows it to evade the innate immune onslaught — another bullet dodged.

What happens within weeks to months after your untreated, inadequately treated, or in some cases, adequately treated tick bite.

The Tissue Penetration Trick

OSPc also binds to something called plasminogen, which actives the enzyme known as plasmin. By commandeering plasminogen, Bb can activate plasmin, which it then uses to break down tissue barriers and clear the way for deeper tissue invasion. That’s not all. Plasmin activates other enzymes known as collagenases and matrix metallproteinases. These bushwhackers help Bb penetrate the otherwise impenetrable tight junctions that protect your tissues from unwanted guests.

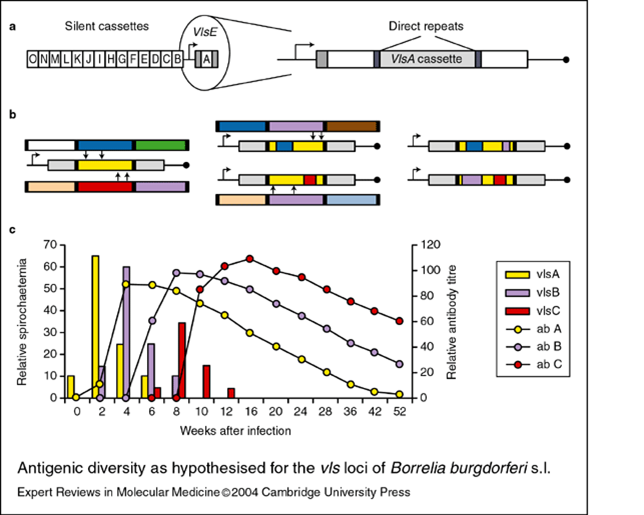

The Technicolor Dreamcoat Trick

At any given time Joseph’s Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat would look completely different. Bb wears a dreamcoat that creates the same effect via an antigen switching mechanism. Another Bb outer surface protein called VlsE is readily detected by your immune system. Each of the many VlsE antigens are processed and presented to your T helper cells, which translate the information to your antibody-producing B cells. The IgG antibodies made by those B cells then patrol the streets for any sign of their particular antigen target. Unfortunately, Bb has a gene that codes for endless VlsE antigen variations. This means fewer antibodies are made per variant. The recombination of VlsE antigens occurs continuously throughout an infection. The result is a weak, poorly focused antibody response against Bb.

The VlsE antigen targets may disappear by the time each specific antibody group starts its patrol, leaving the B cells with nothing to do but cause traffic jams within your lymph nodes, confused about not finding the antigens that they were trained to detect. No wonder antibody tests for Lyme disease are so unreliable.

The Hide-and-Seek Trick

Electron and atomic force microscopy methods have documented that Bb exist in at least two physical forms: the squiggly spirochete morph and the round body morph. The latter is commonly referred to as the cystic form, however, very recent work by Leona Gilbert and her team at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland have shown that round body outer membranes are not cystic in nature and that they’re composed of phospholipids.

Bb round bodies are composed of 6 to 12 spirochetes rolled up together like a ball of yarn tucked inside an outer phospholipids membrane. They go into suspended animation, remaining viable by mooching nutrition from their surroundings. This creates a treatment problem because antibiotics that kill or disable the spirochete forms will induce the surviving spirochetes to hide as round bodies. When this happens, the patient may feel better because round bodies aren’t causing inflammation. Yet if treatment stops, the spirochetes in the round bodies may reactivate, causing the return of inflammation and symptoms.

This is why the antibiotic treatment strategy for persons with Lyme disease should include one antibiotic to cover spirochete forms and another to cover round body forms.

The Pokemon Card Trick

Despite being in a state of suspended animation, the spirochetes within round bodies are taking advantage of a well-known process called horizontal gene transfer. Every Lyme spirochete carries 21 suitcases of extra DNA acquired by this process. In microbiology these suitcases are called plasmids. So within round bodies dormant spirochetes are trading genes like Pokemon cards to obtain new powers against their mammalian hosts. We strongly suspect that one of these powers comes from DNA that codes for biotoxins.

Although more work needs to be done to identify these toxins, we have indirect evidence regarding patients with post-treatment Lyme syndrome (PTLS). Patients with PTLS have these things in common: a) they met CDC criteria for a diagnosis of Lyme disease, b) they underwent aggressive antibiotic therapy that would be expected to “cure” the infection, and c) despite undergoing aggressive antibiotic treatment, PTLS patients remain highly symptomatic. Yet Dr. Shoemaker’s work indicates that treatment designed to bind and remove biotoxins from the body can relieve the persistent symptoms suffered by PTLS patients.

The Persister Cell Trick

Kim Lewis and his team at Northeastern University in Boston reported that the Bb species has the ability to form persister cells. Yet to be published, their study found that 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 100 Lyme spirochetes have the ability to persist despite antibiotic challenge. This ability is found in a wide range of bacterial species. Persisters survive antibiotics by, you guessed it, going into suspended animation. If a Lyme spirochete is neither reproducing nor metabolically active as evidenced by gene expression or protein synthesis, then most antibiotics won’t work.

Lyme spirochetes do not yet carry the gene that codes for antibiotic resistance. But your infection with Lyme spirochetes may persist because a small number of these bacteria can tolerate aggressive antibiotic treatment by laying low and being still, remaining viable by pilfering nutrition from its host. The good news is that by going unnoticed, persister cells cause little to no inflammation. The big question is, what signals will induce Lyme persister cells to reactivate?

Based on mouse studies, we know of two signal types capable of reactivating Lyme persister cells. Emir Hodzic and colleagues at UC Davis showed a few months back that in mice that were infected with Lyme spirochetes and were later aggressively treated with intravenous antibiotic, no evidence for surviving spirochetes could be found until 12 months later, when they placed 40 sterile deer tick larvae on each mouse. When they looked into the bellies of the fed ticks, they found the same strain of Lyme spirochete that they used to infect the mice. In other words, Lyme persister cells can be reactivated by signals that indicate there’s a bus at the station offering a chance to make your way into a new and perhaps friendlier host.

Heta Yrjänäinen at the University of Turku in Finland showed a few years ago that, in a mouse study design similar the one used by Hodzic et al., after finding no signs of spirochete survival after aggressive antibiotic treatment, the spirochetes were detected after the mice were treated with an anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agent. In other words, immunosuppression using the mouse version of Humira, Enbrel, or Remicade, created signals akin to “fewer cops on the beat,” which induced Lyme persister cells to reactivate and potentially cause inflammation in the mice.

This finding carries with it an important implication for the treatment of patients with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. It’s likely that some patients with autoimmune disease also have persistent Lyme disease, and that this may go unrecognized in a medical culture that downplays the possibility of persistent Lyme disease. If such patients are treated with anti-TNF agents and they get substantially worse instead of better, this could be interpreted as evidence for underlying Borreliosis and/or tick-borne co-infection(s) in patients with autoimmune disease.

Though we have so much more to learn about Lyme spirochetes, these bacterial marvels are earning the respect of microbiologists around the world for their arsenal of immune evasive tricks. The more we learn, the better we’ll get at treating this complex infection.

Keith Berndtson, M.D. is a Shoemaker certified physician who practices at Park Ridge MultiMed in Park Ridge, Ill. Dr. Berndtson completed a Lyme disease training program sponsored by the Tick-Borne Disease Alliance and is now a leading Lyme resource in the Midwest. He finds that many Lyme patients non-responsive to treatment suffer from mold toxicity. For more information, visit http://www.parkridgemultimed.com or call (847) 232-9800.

To read Dr. Berndtson’s Review of Evidence for persistence and immune evasion in Lyme disease, visit http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23637552

Featured Resources for Shoemaker Protocol

Better than Resolutions

Every year when the New Year rolls around, people begin to make goals and resolutions to be more health-focused, especially after a busy, festive holiday season.

No luck finding a Shoemaker Certified Practitioner? Here are some solutions:

The top inquiries to our site continue to be, ‘”Is there a Shoemaker Certified Practitioner near me? And, “Is there one who also takes my insurance?” While we don’t have practitioners in every region as of yet, many certified practitioners are set...

Online Proficiency Partners Course

Join a life-changing team helping patients with CIRS recover and thrive.

2016 Third Annual Conference Irvine, CA - Dale Bredesen, MD - Alzheimer's and CIRS

Dr. Bredesen has made GROUND BREAKING progress in reversing the affects of ALZHEIMER'S Disease. In this brief video, you can see the highlights of his speech, tomorrow he will go on NBC's Today show to reveal this massive find. Get more info, the details ...

Review: State of the Art in Mold, Water Damaged Buildings and CIRS Conference. Phoenix, AZ

November 12-15, 2015 By Jonathan Lee Wright I have just returned from four days of attendance at the State of the Art in Mold, Water Damaged Buildings and CIRS Conference in Phoenix, a symposium organized by groundbreaking medical research practition...

.jpg)